“My first impression on seeing him (Grothendieck) lecture was that he had been transported from an advanced alien civilization in some distant solar system to visit ours in order to speed up our intellectual evolution.”

Marvin Greenberg

I was very hesitant about writing this article, for the fear that my ignorance of logic and philosophy might prompt me to say something stupid and embarrass myself. Nevertheless, I couldn’t resist the temptation. For a long time I’ve wanted to explore this idea: imagine an alien civilization on a distant planet in a solar system millions of lightyears away which is advanced enough to have developed their own “mathematics”. What would their mathematics be like? To break this down into several smaller questions: firstly, what would their formal logical system (to make things interesting, we assume they do use one) be like; secondly, what would the mathematical objects they study be like; and thirdly, what would their theorems be like? These “aliens” need not be literal. You can think of “aliens” as a metaphor for an abstract agent, not necessarily literal aliens living in our universe, capable of advanced reasoning but possibly in a drastically different fasion.

Firstly, what if the aliens experience the world differently? I’d imagine if the alien’s body is made of gas, plasma, or some spooky quantum-y matter, they would probably have a much more esoteric perception of the notion of distance. Perhaps even non-archimedean distance is more natural to them? Maybe they discover \(p\)-adic numbers before they discover real numbers? In human history, real numbers and the rigorization of calculus (real analysis) is central to the development of foundations. Perhaps \(p\)-adic numbers would play a similar role in the alien’s development of mathematical foundations, leading to different definitions of these structures? On the other hand, what if the aliens live in a universe where the laws of physics is different? This may affect their concept of many fundamental notions, such as space or shape. Their perceptions of causality may also affect their concept of probability, and so on.

Secondly, what if the alien’s intuition, that is, the way their brain works, is different? In Liu Cixin’s Remembrance of Earth’s Past scifi trilogy (spoilors!), he described an alien civilization, the trisolarans, who spontaneously and instantaneously communicate their thoughts through electromagnetic waves. To the trisolarans, thinking is the same as speaking, and therefore they have no concept of deception, which gave them a big disadvantage against humans when they invaded earth. Similar things might be true for math. When I was learning algebraic topology for the first time, I found the calculations of fundamental groups and homology groups using Seifert–van Kampen theorem and Mayer–Vietoris sequences particularly interesting. Compared to other proofs I did, they seem to depend highly on pictorial intuition. This kind of intuition is especially common in the study of low-dimensional topology, where mathematicians often work with pictorial intuition before writing down rigorous proofs. A general observation seems to be that the more intuition we have of something, the less reliant we are on its formalisms. One could imagine that there might be aliens who are able to perform this kind of informal intuitive argument on higher dimensional or non-archimedean spaces (e.g. rigid analytic variety), which we mere humans can only approach with rigorous formalism.

Thirdly, what if the aliens have different societal influences on mathematics? For example, in human history, the development of various number systems, from \(\mathbb N\), to \(\mathbb Z\), to \(\mathbb Q\), and to \(\mathbb R\), is rooted in our demands for increasingly sophisticated mathematical structures in socioeconomic production such as accounting and engineering. From counting discrete finite things with natural numbers, to including negative and rational numbers for the purpose of representing money, and to including numbers arising in geometry such as \(\pi\) and square roots (arising as length of hypotenuse of right triangles), and so on. An alien society with possibly different socioeconomic demands may lead to a different line of development of number systems, or perhaps they didn’t start with \(\mathbb N\) to begin with! The study of number systems begat the study of abstract rings, hence one could imagine aliens having different axioms for rings. And this could be said about many other mathematical structures and their abstractions. On the other hand, the influence of natural languages in math can’t be ignored. First-order language came from our natural languages. One expects aliens to have different natural languages, which could influence the rules of their formal languages.

The more I ponder about these possibilities, the more I believe that human mathematics is by no means natural or unique epistemologically – there are a lot of things in our math that are rather arbitrary. Aliens could disagree with us on what mathematical objects are more basic, which elaborations of the basic objects are more natural, which body of mathematics is more intuitive, which mathematical structures better capture fundamental notions, and so on.

A much more challenging question is, what would be universal among all alien’s (and our) math? Here, I propose a candidate answer to this question: abstractions (i.e. concepts or definitions). From an early age we learn to count things with our fingers, but what we are really doing is establishing a bijection between our fingers and the things we are counting. We do this because we realize that counting is the same mechanism regardless of the thing we are counting. Counting our fingers and counting anything else are isomorphic! The natural numbers is the abstraction of this mechanism. I think it is fair to assume that any kind of alien math would certainly incorporate this idea. I do not believe that there are aliens who do math by mechanically generating theorems from axioms using inference rules (and if so, it is debatable what they are doing is actually math). There must be a point where they introduce concepts and definitions of mathematical objects. They are what really matters. This brings me to the question: in order for aliens to talk about concepts and definitions rigorously, is it absolutely necessary for them to establish a reductionist axiomatic framework similar to ours (such as Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory)? Here, by reductionist I mean in a similar sense to reductionism in the philosophy of science, that is every statement is derived from a common set of axioms, and every objects is constructed from “a priori” objects (e.g. sets).

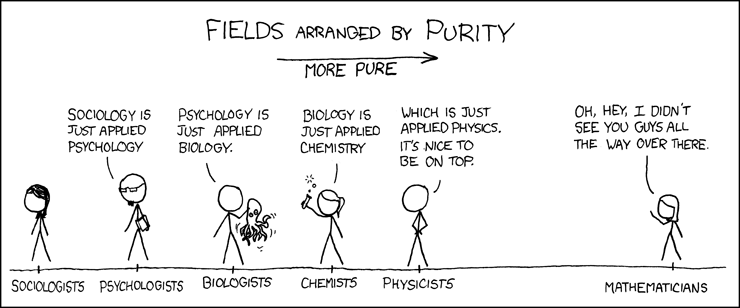

Reductionism, more generally speaking, is the belief that things can be explained by breaking them down into smaller more fundamental things. A quintessential reductionist belief is, chemistry is just applied physics, biology is just applied chemistry, etc.

Reductionism has been criticized by many, but most famously by theoretical physicist P. W. Anderson in his More is Different. In a nutshell, Anderson argues that “the main fallacy of this idea is that the reductionist hypothesis does not by any means imply a constructionist one: the ability to reduce everything to simple fundamental laws does not imply the ability to start from those laws and reconstruct the universe.” Another more sophisticated criticism comes from W. V. O. Quine, in his Two Dogmas of Empiracism, which argues that there is inherently a kind of circularity when trying to implement reductionism. This made me think that, perhaps, similar to empirical sciences, the fact that we can reduce mathematical structures to more basic constructions, doesn’t imply that we necessarily have to reduce everything to a common set of axioms (or reduce every construction to sets).

It seems to me that, to mathematicians whose work lie in traditional fields such as number theory and geometry, perhaps excluding those more philosophically sophisticated, the foundations of mathematics are viewed with pure utilitarianism, if not sheer nonchalance. For them, the foundations are merely instruments to clarify and rigorize mathematics, and it is almost never the case that they consider a formal foundation of math an ontological characterization of mathematics. It seems as if that many mathematicians assume the axiom of choice, or some other axioms of ZFC, primarily because the theories they already informally have, whose substance often has little or nothing to do with the set theoretic foundations on which they are built, demand them. In this sense, axioms of our foundations of math are ad hoc!

Mathematicians are justified in thinking this way. When doing mathematics, they do not typically think in pure logic. Instead, they operate on a level much beyond pure logic: they often come up, from intuition and experience, with a rough outline of (often ambiguous) reasoning prima facie, and then write them down formally and fill in the details to check if they are correct — much analogous to how physicists check their theories empirically. It is therefore easy to see why so many pure mathematicians are attracted to Platonism — it feels like they are discovering mathematics, not inventing it. I believe that this is the source of their utilitarianism in foundations — if what we are doing is discovery, then it makes no sense to demarcate what we could or could not discover. Philosopher Gottlob Frege famously compares the work of a mathematician to that of a cartographer. The cartographer picks the parameters of the map (the scale of the map, the type of projection to use, the color of each region, and so on), but the cartographer does not invent the actual geography.

I wonder whether there is an “axiom-free” approach to the foundation of math, in contrast with the orthodox view that the edifice of math stands upon a solid agreed-upon base? Maybe we could forgo the view that an a priori notion is needed to build others, and allow a multitude of “a priori notions”? How do we ensure that one works well with another? Ay, there’s the rub! These questions have become too difficult for my current level of mathematical maturity, and I think this is a good point for me to stop rambling my nonsense.

Comments